In 1964, an interesting Roman inscription was discovered during ploughing at Branston, four miles southeast of Lincoln. Of ‘ansate’ form (referencing the handle-like decorative elements either side of the inscription), the stone measures 92cm x 50cm and forms a monument for a girl named Aurelia Concessa.

The neatly cut inscription is incomplete, missing a diagonal section on the right hand side, but can still be read. The scored guidelines to assist the stone carver can still be clearly seen. The inscription reads:

IN HIS PREAD(I)[IS]

AVREL(IAE) CON[CE]/

SSAE SAN[CTIS]/

SIMAE PV[ELLAE]

This translates as ‘In this estate. For Aurelia Concessa, a girl most virtuous.’ This seemingly simple message belies more complicated clues to the potential origins and cultural heritage of Aurelia and her family.

The inscription, although a memorial to the deceased, was not a grave marker denoting the resting place of her remains. Instead, it was intended to be inserted into a larger memorial monument. This, combined with the reference to her remains being buried ‘in this estate’ suggest to us an extensive farm or villa complex, large enough for such a memorial to be constructed, perhaps in a prominent location or a place with particular significance to Aurelia herself. The use of the specific phrase ‘in his praed(i)is‘ is a significant one as, despite being common in continental inscriptions, it is currently unique in Britain (Wright 1965; Tomlin et al 2009). It suggests that Aurelia not only lived on the estate, but was part of the owning family. Wright suggested that an unwritten extension to the phrase might have been ‘ossa sita sunt‘ – giving the more complete phrase ‘in this estate lie the bones…’. Noting that this phrasing occurs several times in inscriptions from Campania, on the southeastern Italian coast, Wright suggested that the family’s origins lay in that part of the world. Although Tomlin et al have subsequently moved away from such a precise interpretation, the suggestion that the unique use of this phrase in Britain indicates a family grouping bringing their own traditions with them remains valid. So close to Lincoln, an obvious (though unprovable) interpretation might be that it represents a military veteran and his family.

The inscription tells us little of Aurelia herself, except for referencing her virtuous nature. The use of the term ‘puella‘ – meaning ‘girl’ might lead us to think that Aurelia was a child and her memorial erected by grieving parents. Tomlin et al (2009), however, noted that the form of the compliment (virtue-ssimae) occurs in Britain exclusively in epitaphs honouring deceased wives (referencing RIB507, RIB1828, RIB2006 and RIB3398 as parallels). Should we therefore instead see Aurelia as a young wife and perhaps the lady of the estate?

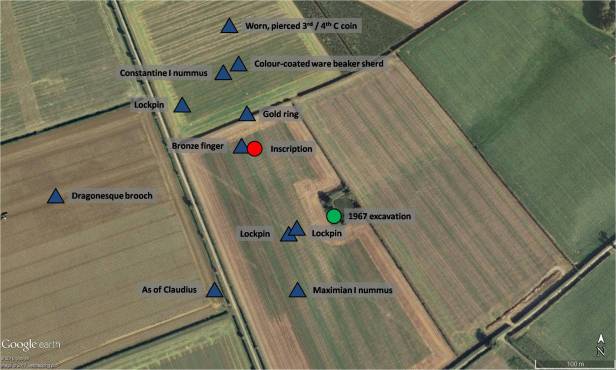

The nature of the estate and buildings that Aurelia knew remain a mystery. Following the discovery of the inscription, a small excavation was carried out in an adjacent field (see the map below) in 1967 by a Mr J. T. Hayes (Whitwell and Wilson 1968). An irregular stone foundation was discovered, interpreted as the remains of a stone and timber building, along with charred timber, nails, pottery, roofing tile, flue tiles and tesserae. An amphora sherd stamped ‘EROTIƧ’ was also found, dating to between AD50 and 120 (Whitwell and Wilson 1969). These are indicative of sizeable buildings in the area, but it is still not possible to say what the nature of the structures was.

In more recent years, the Portable Antiquities Scheme has added new evidence, including some extremely interesting finds made very close to the spot where the inscription was discovered.

In 2009, a life-sized copper alloy finger was discovered at almost the exact same spot as the Aurelia Concessa inscription. The break is clean and patinated, suggesting that it was a deliberate act carried out in antiquity. The finger could represent a sculptural bronze element to the memorial to Aurelia Concessa, though this would mean the structure was on a grand scale, and we might expect more remains to have survived if this were the case. Instead, the finger might be votive in nature. Anatomical votive offerings are well attested at shrine sites across the Greek and Roman world. If this is the case, why might it have been deposited here?

Other finds in the area might also be interpreted as appropriate offerings at a shrine. A gold finger ring of 3rd Century date was discovered c.60m to the north of the inscription in March 2016, and three copper alloy lockpins have been found to the northeast and southwest. These latter finds are bell-shaped copper alloy terminals with iron shanks, used as part of locking mechanisms, perhaps on decorative boxes. Although discovered in many contexts across the country, they are known from Coventina’s Well, a ritual site at Carrawburgh on Hadrian’s Wall, providing a parallel for their use as a suitable votive object.

The suggestion of any form of shrine at the site of course remains extremely speculative, but the assemblage is worthy of note, and the association of the inscription and the surface finds has not been previously noted. Might the structure excavated nearby in 1967 have formed some form of simple rural shrine? If so, we have to ask whether the construction of a monument to Aurelia Concessa was in relation to that shrine, or whether the shrine may have been established as a result of the monument. Perhaps Aurelia’s virtue was recognised as a source of inspiration even after her death.

References

Tomlin, R.S.O. et al. 2009. The Roman Inscriptions of Britain Volume III: inscriptions on stone. Oxbow

Whitwell, B. and Wilson, C. 1968. Archaeological Notes for 1967. Lincolnshire History and Archaeology Vol 3

Whitwell, B. and Wilson, C. 1969. Archaeological Notes for 1968. Lincolnshire History and Archaeology Vol 4

Wright, R.P. 1965. Roman Britain in 1964: Inscriptions. Journal of Roman Studies Vol LV

I delight in, cause I discovered exactly what I used to be looking for. You’ve ended my four day lengthy hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day. Bye

LikeLike

You really make it appear so easy with your presentation but I to find this topic to be really something which I believe I’d by no means understand. It sort of feels too complex and extremely large for me. I am looking forward for your next submit, I will try to get the cling of it!

LikeLike