I had the opportunity recently to assess the condition of some of the Roman shoes excavated at Lincoln’s Roman waterfront in the late 1980s. The excavations, which I’ve mentioned before in this post about an enigmatic wooden paddle, have provided some of the best organic survival in the city, but have never been fully published and sadly remain less known than they should be.

The British site best known for producing well-preserved Roman shoes is Vindolanda, the fort just south of Hadrian’s Wall. Excavations there have produced thousands of shoes over the years, many of which are in near perfect condition. The quality and quantity of finds do present something of a conservation problem, though, and they currently have an appeal to help conserve the latest finds.

Shoes came in a variety of shapes, sizes and designs during the Roman period, from the famous robust military boots known as caligae, famous for being the basis of the Emperor Caligula’s nickname, to soft leather slippers, fashionable ladies’ wear and children’s shoes. Many outdoor shoes had tough hobnails in the soles to help with durability and provide grip on muddy surfaces, and shoes could have elaborate openwork sides, perhaps even designed to show off colourful socks underneath. The leather was usually from cows or goats, and the shoes we find are often from contexts where they were discarded, worn and broken.

That was the case with the assemblages of shoes from Lincoln’s waterfront, where they were caught up with rubbish layers used to reinforce the riverbank. Whether casual losses from people dangling their feet over the side, the result of people deliberately throwing shoes into the water to dispose of them, or brought there when waste pits from elsewhere in the town were dug up and used in engineering works, the anaerobic conditions of the river enabled them to survive when many, many more have not.

The study of Roman shoes is actually rather interesting, and those wishing to look in more detail at the social and even religious connotations of feet and shoes may wish to look at Carol van Driel-Murray’s paper ‘And Did Those Feet in Ancient Time… Feet and Shoes As a Material Projection of the Self’, presented at the Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference in 1998. Hobnailed boots, for example, often get found in burials (see here for an example from Sleaford in Lincolnshire) and footprints are known on ceramic tiles (see here for a child’s footprint on a tile from Lincoln).

I am not going to write about each shoe in detail, and would rather let the images speak for themselves. Particular favourites of mine, though, are the child’s hobnailed shoe (WO89 /276\) and the soft leather sandal with openwork traces on the upper (WNW88 /1699), the sole worn through in two places and doubtless the reason why it was discarded. These little touches, so familiar to us today, remind us that these shoes were once the property of people just like us.

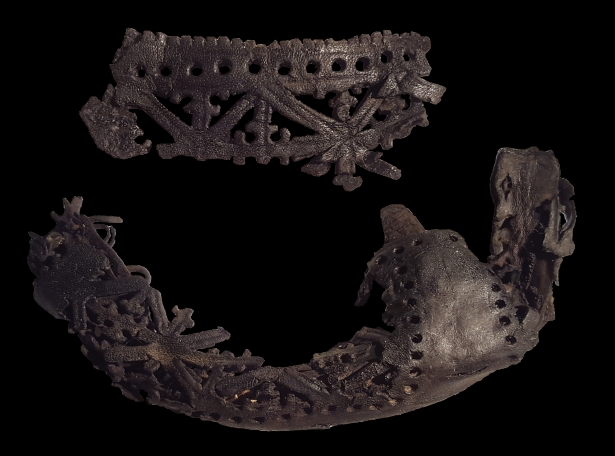

Sometimes, a shoe that doesn’t survive in good condition can still give an idea of how decorative it originally was. The shoe below sadly now only survives in two small fragments, but these demonstrate the delicate leatherwork of a fashionable sandal.